Service Members are at increased risk for musculoskeletal injuries, trouble sleeping, high levels of work-related stress, and obesity, among other issues. These risks can lead to poor performance and health. To reduce your risk, you can often improve your Total Force Fitness and optimize your performance by changing some of your behaviors.

But how ready are you to change? For behavior change to be successful, you first need to identify exactly which behavior you want to change. One way to do that is to set a SMART goal—Specific, Measureable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time sensitive. For example, instead of saying, “I will try to change my stress level,” you would say, “I will meditate for 10 minutes right before bed, every day for 30 days, to reduce stress and help me sleep.” From your SMART goal, you can think about next steps, such as your readiness to make that change.

Measure your readiness to change

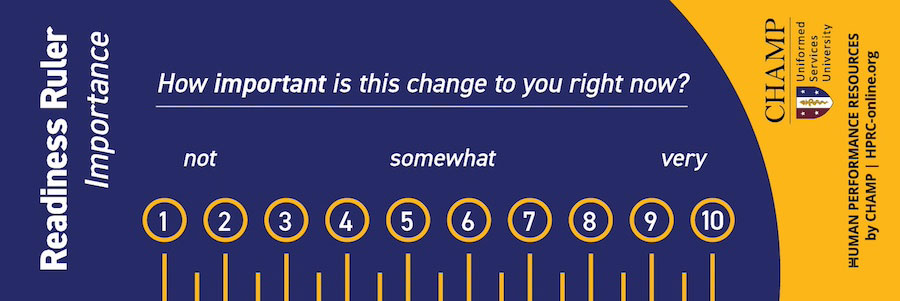

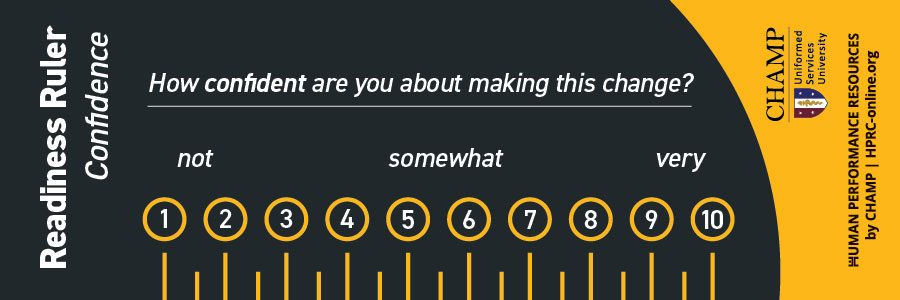

A readiness ruler is a tool to help you assess your readiness to change. The readiness ruler assesses 2 components of behavior change readiness: importance and confidence.

- Importance refers to how important making the behavior change is to you.

- Confidence refers to how confident you are that you can make the behavior change.

Use the readiness ruler to reflect on your current behavior and express your desire to make a behavior change. Even if you have mixed feelings about wanting to change or you’re in the early stages of planning, you’re more likely to change your behavior if you explain in your own words your desire to change.

Importance

Answer the question, “How important is this change to me right now?”

If you rated the importance of needing to change at a 7 or higher on the ruler, then you’re probably ready to change. You can boost your chances of success even more by making sure you have access to sources of support, such as your installation’s resilience coordinator, this resources finder, or HPRC’s recommended resources at the end of this article.

If you rated the importance of changing lower than a 7, then you might not be ready to change. That’s okay. It might not be the right time for you to change, and you shouldn’t feel pressured if you aren’t ready. It’s also possible you might not have accurately identified your behavior change goal. For example, maybe you originally identified meditation as a way to reduce stress and improve sleep. But if starting to meditate isn’t actually the change you want to make, you might think the importance of this change is low. Changing your goal to something more accurate, such as taking daily walks outside or reducing social media usage to reduce stress and improve sleep could help boost your rating.

Consider the following questions to help you increase how important it is for you to change your behavior:

- Why did I choose the current number and not one number lower? Example: Why a 4 and not a 3?

The question is designed to prompt an explanation about why the change is important. Comparing between the current number and a lower number helps you frame the importance of this behavior change positively.

- What would it take to get from the current number to one number higher? Example: What would it take to get from a 4 to a 5?

Reflecting on the comparison between the current number and a higher number can help you think about taking action. Even a small, actionable step can increase motivation to change behavior. Thinking about what it would take to increase your rating of why this change is important can also help you identify whether the goal you chose associated with the behavior change is accurate. This question can help you clarify which specific action might make you better able to change your behavior.

Confidence

Answer the following question: “How confident am I about making this change?”

If you rated your confidence to change at a 7 or higher, then you’re probably ready to change. Ensuring you have access to sources of support and resources can help you be successful in achieving your goal.

If you rated your confidence to change at lower than a 7, then you might not be ready to change. Again, that’s okay. You might feel there are obstacles preventing your behavior change or making it more difficult to achieve. Identifying any obstacles to changing your behavior can lead you to seek out resources and referrals to help you overcome those obstacles.

Consider the following questions to help you increase your confidence to change your behavior:

- Why did you rate your confidence to change at the current number and not one number lower? Example: Why a 5 and not a 4?

By comparing the current number to a lower number, you can figure out what small steps you’re already taking to change your behavior. This highlights your ability to change your behavior and helps put you in control of making changes.

- What would it take to get from the current number to one number higher? Example: What would it take to get from a 5 to a 6?

Again, thinking about the comparison between the current number and a higher number can get you one step closer to taking action. Achieving small, actionable steps can increase confidence in successful behavior change. In addition, reflecting on this question can help you spot any obstacles that could prevent successful behavior change.

Consider this example:

Service Member Smith has been having 6 (alcoholic) drinks per night, 5 nights per week. Smith is feeling burned out and unmotivated at work, hasn’t been sleeping well at night, and has noticed more conflict in his relationships. Smith realizes he needs to cut down on his alcohol consumption to improve his performance.

Smith sets a SMART goal to reduce his alcoholic intake to 2 drinks, 3 nights per week or less, for 1 month. With this specific goal in mind, he can state how important this change is to him and how confident he is that he can make this change.

Smith looks at HPRC’s readiness ruler to help him think about behavior change. Here are some sample questions Smith might ask himself when he considers how important it is to drink less alcohol—and how confident he is he can change his behavior by cutting back how much he drinks each week:

Importance

How important is drinking less alcohol to you right now? Smith’s rating: 9.

Why a 9 and not an 8? Smith’s answer: “I see how my current level of drinking is hurting my work performance and my relationships.”

What would it take to get you from a 9 to a 10? Smith’s answer: “I don’t want to experience the negative consequences of my current behavior, such as an evaluation that could hurt my promotion or a breakup. Just the threat of those consequences gets me closer to a 10.”

Confidence

How confident are you that you can cut down on your drinking? Smith’s rating: 5.

Why a 5 and not a 4? Smith’s answer: “Since I’m not cutting out alcohol completely, this seems like a change I could make.”

What would it take to get you from a 5 to a 6? Smith’s answer: “It would take knowing I have support from my friends to make this change for my health and performance. I enjoy the social aspect of hanging out with my friends, but I feel pressure to drink with them. So knowing I have their support to drink less would get me to a 6.”

Although the readiness ruler can help you assess your readiness to change, remember that behavior change can be difficult! It can be difficult to get started, and there are often setbacks and barriers to overcome along the way. Be patient, yet persistent! Take advantage of the many resources available to help you improve and maintain your performance, health, and well-being. Use HPRC’s Total Force Fitness resources handout to jot down the resources most applicable to you.

Additional resources:

- Better sleep

- Healthy nutrition

- Injury prevention

- Mental health care

- Speaking with military chaplains

- Stress management

- Suicide prevention

- Tobacco cessation

Note: This readiness ruler is designed for self-reflection, not as a clinical diagnostic tool.