Shoulder pain and shoulder injuries are among the most common reasons Service Members sought medical attention in 2019. Most shoulder injuries are classified as general pain, but more serious injuries include dislocations and separations. Preventing shoulder injuries requires you to understand a little bit about joint anatomy and how most injuries happen. In addition, here are some tactics to add to your workouts.

Shoulder anatomy

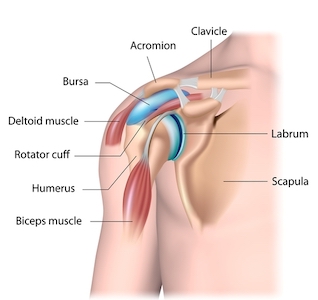

The shoulder joint is called a “ball and socket” joint. It is made up of 2 bones that create the socket: the scapula (shoulder blade) and clavicle (collar bone). The humerus (upper arm bone) is the “ball” that sits in the socket. This type of joint allows you to move and twist your arm in a large range of motion. The downside of having such a large range of motion is that it is less stable than other types of joints, for example the knee or ankle.

The shoulder joint is called a “ball and socket” joint. It is made up of 2 bones that create the socket: the scapula (shoulder blade) and clavicle (collar bone). The humerus (upper arm bone) is the “ball” that sits in the socket. This type of joint allows you to move and twist your arm in a large range of motion. The downside of having such a large range of motion is that it is less stable than other types of joints, for example the knee or ankle.

The humerus is attached to the scapula by several ligaments and 4 small muscles that make up the “rotator cuff.” The rotator cuff is responsible for starting movements such as lifting and rotating your arm and pulling the humerus into the socket to keep it stable. Finally, there is a small, fluid-filled sack called a bursa that sits in the joint between the top of the humerus and below the part of the scapula called the “acromion.” Shoulder pain often comes from this area.

Common shoulder injuries

Shoulder injuries can present in a variety of ways. Here are 3 of the more common injuries and what causes them.

Shoulder impingement

A shoulder impingement happens when the bursa and one of the rotator cuff tendons become pinched, or “impinged,” between the top of the humerus and the acromion. If it is caught early enough, there isn’t usually much physical damage, but it can be very painful when you lift your arm overhead.

Shoulder impingements are most often caused when the muscles that attach your scapula to your back and shoulders are weak and stretched out due to bad posture. As you raise your arm, the muscles can’t work as well to move your scapula, causing bones to grind on the bursa and rotator cuff. A shoulder impingement can be corrected with postural exercises that help position your shoulders back and move your scapula properly.

Rotator cuff tendinopathy

Rotator cuff tendinopathy—or tendinitis, as it used to be called—is when your rotator cuff tendons start to break down due to overuse. It is most common in the supraspinatus tendon, which attaches at the top of the humerus. It gets impinged and can start to fray, like a rope that gets rubbed against something for too long. Constant impingement doesn’t allow the tendon to heal, and it can get progressively worse over time. If the impingement is corrected, the tendon can heal and resolve the pain. If the pain gets bad enough, surgery might be required to fix it.

Shoulder dislocation

When you dislocate your shoulder, the humerus gets pulled from the socket, tearing one or more of the ligaments attached to it. Most shoulder dislocations are “acute injuries,” or injuries that happen quickly from a single action. Because dislocations are acute injuries, they can be hard to prevent.

Some people have shoulder instability, which is a result of a previous dislocation or a genetic predisposition. These people are at greater risk for dislocations. This type of instability is difficult to manage, and it can be hard to prevent future dislocations.

How to prevent shoulder injuries

Since most shoulder pain is caused by impingement at the top of the shoulder, prevention exercises focus on improving posture and scapular mobility. Poor posture (for example, from sitting at a desk all day) results in rounded shoulders and your head being pushed forward. The general rule of “stretch the front, strengthen the back” applies. Focus on stretching your chest and neck. Target the rhomboids and the middle and lower trapezius (the muscles in your upper back), also known as scapular stabilizers. Those muscles pull your shoulders back and properly rotate your scapula as you lift your arm.

The next set of exercises focuses on stabilizing the humerus in the joint, mainly by strengthening the rotator cuff. V-raises and shoulder rotations are two exercises that can improve stability over time. If you do not currently have shoulder pain, the Rx3 Shoulder Phase 3 exercise program works as an injury-prevention program. If you do have shoulder pain, be sure to get it checked out by medical. Start at Phase 1 if Rx3 is recommended by your provider.

When you perform these exercises, focus your training strategy on improving muscular endurance. The main purpose of the shoulder muscles is to make small movements and hold positions for long periods of time. They are not designed to lift heavy weights. For scapular-stabilization exercises, you can use weights ranging from zero to 3 pounds and still get in a good workout.

Try to do these exercises at least 3 days a week at first. Then as you build endurance, you can do them only on the days you do an upper-body workout. The longer you do these exercises, the better they’ll work!

Find out how to work out around exercise limitations Learn More

Find out how to work out around exercise limitations Learn More