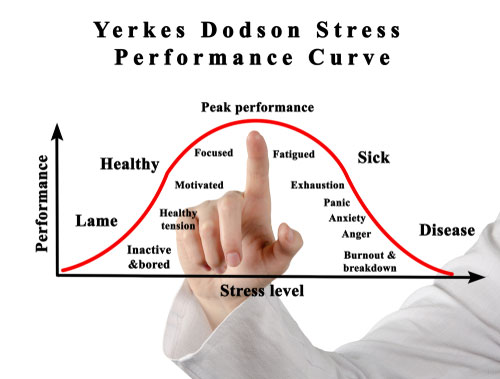

For each specific performance, Military Service Members have a certain “right” amount of energy they require from their stress response system that enables them to perform at their best. This is often known as your individual zone of optimal functioning (IZOF). With too little energy from your stress response system, you won’t be engaged enough. However, if you have too much energy from your stress response system, you might lose focus and control and break down. This “right” amount of energy is different for each person and each task. For example, an upcoming work deadline, your child having trouble with other kids at school, a car accident, or a passionate kiss from your partner will all activate your stress response system, but each requires a different level of energy, focus, and emotion for you to be at your best. Keep in mind what allows you to perform at your best while giving a brief looks different from what enables your battle buddy to do the same core task.

For each specific performance, Military Service Members have a certain “right” amount of energy they require from their stress response system that enables them to perform at their best. This is often known as your individual zone of optimal functioning (IZOF). With too little energy from your stress response system, you won’t be engaged enough. However, if you have too much energy from your stress response system, you might lose focus and control and break down. This “right” amount of energy is different for each person and each task. For example, an upcoming work deadline, your child having trouble with other kids at school, a car accident, or a passionate kiss from your partner will all activate your stress response system, but each requires a different level of energy, focus, and emotion for you to be at your best. Keep in mind what allows you to perform at your best while giving a brief looks different from what enables your battle buddy to do the same core task.

Help yourself stay in your stress “sweet spot” by using these 3 steps to ensure you have the right amount of energy for peak performance.

- Name the stress. This helps you break out of the primitive (reactive) part of your brain and use the part that helps you plan and reflect.

- What are you feeling, doing, and focusing on? What’s your self-talk?

- Embrace the stress. You’re experiencing stress because something you care about is in play and your body is trying to give you the energy needed to live it out.

- What goal or value makes this important to you?

- Channel the stress. Use the energy your body is providing to intentionally improve your performance for the task at hand.

- What’s the best way to use your energy to help achieve that goal or value?

- What do you need to do, feel, or focus on?

- What do you need to say to yourself to get there?

If stress is too high, activate your relaxation response system

Stress can enhance your performance, health, and ability to learn and grow. But when you’re stressed too often, too extreme, or for too long, it can have a negative impact on your health, performance, and resilience. When your stress response is on overdrive, you might exert more energy than is ideal for you to perform at your best. Sometimes you might need to pump the breaks on your stress response system to help you get into your stress sweet spot that will enable you to perform well. Luckily, your body has a relaxation response system you can learn to use to calm yourself down and focus your energy to maximize performance. Even better, there are relaxation response skills you can master in the moment to lower your stress when it’s getting in the way of your performance and give you relief when it becomes unhealthy.

One way you can enhance your performance is to be able to recognize when you’re activating too much stress—that might cause you to feel scattered, overwhelmed, or panicked—and use relaxation response skills to calm yourself down. You can practice these skills prior to a performance to get yourself centered and in the zone. Or you can use them in the moment to regain focus and control. The more you practice these skills, the better you’ll be able to activate them when needed. Plus, you’ll have a better idea of which relaxation response skills work best for you at different times. For example, tactical breathing might be most effective for when you need to calm down in the moment or on the range, while mindfulness meditation is better for you prior to a performance. The more relaxation tools you have in your arsenal, the more likely you’ll be able to get the right amount of energy for each task at hand.

Relaxation response skills to help find your stress sweet spot!

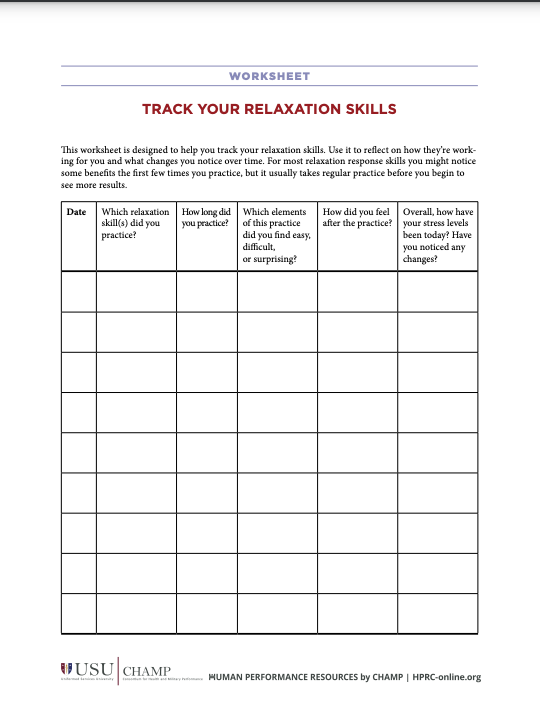

There are several relaxation response skills and resources you can use to improve your performance. Read through the ones below and then click on the links to learn more about the ones you want to try first. Try each skill out for a week and track its impact using the worksheet below. If you don’t like one after you try it, try another one the following week. The goal is to find a few relaxation response skills that you can practice regularly. Regular practice helps you become an expert in a skill, so you can effectively lower your stress levels in the moment and get to your stress sweet spot. Each skill also provides many other health and performance benefits that come with regular practice.

Tactical breathing exercises

Tactical breathing exercises can slow your breathing by using steady, full breaths and longer exhales. Doing this activates your relaxation response, which in turn relaxes your muscles and sends feedback to your brain that all is well. Regular practice can help reduce symptoms associated with anxiety, insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. To learn more, read HPRC’s article on how tactical breathing works.

Progressive muscle relaxation

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is a practice in which you tighten and relax various muscles throughout your body. You can start with your feet and work your way up your body as you tighten each muscle group for 5 seconds and then relax for 20–30 seconds. Do at least 2 or 3 reps for each muscle group—or more if you still notice tension. Regular practice can help relieve the physical symptoms of stress by lowering blood pressure, lessening fatigue, and easing tense, aching muscles. Listen to HPRC’s audio guide for progressive muscle relaxation to learn more.

Mindfulness meditation

Mindfulness meditation is the practice of focusing your awareness on the present moment without judgment. It’s simply being aware of what you’re experiencing now rather than thinking about the past or the future. A common approach is to focus on a physical experience such as your breathing, notice where and when your attention wanders, and gently guide your attention back to your breath. Regular practice can help increase your memory and ability to focus, lower your perception of stress and anxiety, and improve your health. To learn more, listen to HPRC’s audio guide to practice a mindfulness meditation.

Yoga

Yoga combines stretching exercises, breathing techniques, and meditation. There are many different types of yoga you can do at home, outdoors, or at a yoga studio. Regular practice can help release stress, improve sleep, relieve pain, and improve health. Watch HPRC’s video guides to practice yoga to learn more.

Positive emotions

Positive emotions are when you feel gratitude, joy, awe, hope, humor, inspiration, or love. Positive emotions are enjoyable to experience, and they help with stress management. If you’re feeling overwhelmed with anger or anxiety, a boost of positive emotions can help you reset, lower your heart rate, and bring your body back down to baseline to focus on the task at hand. When you make it a regular practice to experience positive emotions, it builds up your body’s stress hardiness. And when you combine gratitude with tactical breathing or mindfulness meditations, you can get double the benefits. To learn more, read HPRC’s tips on how to put more positive emotions in your life and use our Gratitude Calendar.

Positive self-talk

Positive self-talk helps you to grab control of your heat-of-the-moment thoughts and make them productive to get you to your stress sweet spot. At times you might have self-talk that says, “You can’t do this—you don’t have what it takes” or “There’s no hope.” This can put your stress response system into overdrive and undermine your ability to perform. To activate your relaxation response system, you can practice motivational self-talk by challenging counterproductive thoughts with evidence: “I know I can do this because I’ve been training 5 days a week” or “This is my opportunity to turn this around.” You can also use instructional self-talk to focus your energy by stating step by step what you need to do: “What I need to focus on now is see the target…straighten my elbows…lock onto target…and fire.” Positive self-talk might not seem like the other relaxation response skills, but it’s a valuable tool to help you calm down and get to your stress sweet spot. To learn more, check out HPRC’s worksheet on how to optimize your self-talk.

Don’t QUIT! Change your stress mindset. Read More

Don’t QUIT! Change your stress mindset. Read More

Download the Relaxation Skills worksheet below and choose a few relaxation response skills that you think might work for you. Try them out for a week or two and track your results. If they don’t work for you, try another one. The goal is to learn what works best, so you can manage your stress and optimize your performance.