Stress is your body’s way of giving you energy to handle real or imagined challenges. The stress response system is designed to improve physical and brain function to meet impending demands when something that matters to you is at stake, whether a relationship, a goal, or your life. Stress can help you focus your attention on the issue at hand, take initiative, problem solve for upcoming issues, boost memory, and improve processing speed and performance on mental tasks. Stress can also help you learn from challenges, become more mentally tough, develop stronger relationships, reshape priorities, and increase your appreciation for life. All this sounds pretty good.

So why is there so much focus on ridding ourselves of stress? You have likely heard how stress can be bad for you, can decrease performance, and is connected with several of the leading causes of death (heart disease, accidents, cancer, liver disease, lung ailments, suicide).

How can stress be bad and good for you at the same time? It turns out, your belief about whether stress is helpful or harmful plays a vital role in helping you gain the advantages stress can offer. If you believe stress is bad for your health, performance, and ability to grow, then the experience of stress can become a stressor itself—and will likely harm your health, performance, and ability to grow. Yet, simply believing stress is helpful and stress brings out the best in you can help you to improve your performance, health, relationships, and grow from difficult experiences. Learn about your beliefs about stress, how they impact your performance, and get some stress optimization strategies to help you use your stress response to your benefit.

What is your stress mindset?

Answer the following questions to help you reflect on your general beliefs about stress and how you tend to react to it. After you take the survey once, you might want to take it again focusing on specific types of stress, such as stress involving work performance, your partner, family, or health. Your answers will help you target the different strategies provided throughout this article to help you optimize stress.

General beliefs about stress

The effects of stress in most cases are:

- a. negative and should be avoided

- b. positive and should be utilized

Experiencing stress in most cases:

- a. inhibits my learning and growth

- b. facilitates my learning and growth

Experiencing stress in most cases:

- a. depletes my health and vitality

- b. improves my health and vitality

Experiencing stress in most cases:

- a. hurts my performance and productivity

- b. enhances my performance and productivity

General reactions to stress

When I notice the physical responses of stress (such as increased heart rate, sweating, shaky hands or legs) I’m more likely to interpret it as:

- a. “I’m about to lose control.”

- b. “This is my body giving me the energy I need to perform.”

When under a lot of stress, I’m more likely to:

- a. get distracted by my negative thoughts or stuck focusing on things I can’t control

- b. reflect on what’s most important to me in the situation and take purposeful action to bring about my goal/value.

When I’m beginning to feel overwhelmed by stress I usually:

- a. try to escape and distract myself through social media, TV, alcohol, eating, etc.

- b. use a strategy like tactical breathing or mindfulness to center myself and regain focus on the task at hand

When under a lot of stress, I’m more likely to:

- a. isolate myself

- b. reach out to others for help or go out of my way to help others

When under a lot of stress and someone comes to me to share unrelated good news, I’m more likely to:

- a. give them partial attention or dismiss them to get back to what I’m focused on

- b. stop what I’m doing and give my full attention to share in their joy

Benefits of believing stress is helpful

If you chose “b” for most of your answers, then you likely have a “stress is helpful” mindset! Those who believe stress is helpful are better able to use stress to improve their performance, health, and growth compared to those who believe stress is harmful. In a study of 174 Navy SEAL candidates, those who believed stress was helpful had faster obstacle course times, were more highly rated by leaders and peers, and lasted in the program longer than those who believed stress is harmful.

People who believe stress is helpful show better memory and performance on standardized tests. They also have fewer headaches and back aches, and less insomnia and hypertension. Believing stress is helpful might even help you live longer! Those who believed stress was harmful and experienced a great deal of stress had an almost 45% increased risk of premature death compared to people who experience little stress and those who experienced a lot of stress but believed stress is helpful.

If you answered “a” on most questions, you likely have a “stress is harmful” mindset. The good news is, you now have the opportunity to improve your performance, health, and growth by developing a “stress is helpful” mindset. While saying you should develop the “stress is helpful” belief is easy, actually believing it is much more challenging.

Understand how the stress response system works and how it’s impacted by your beliefs.

You might be wondering how just believing stress is helpful can make it good. To understand, first you need to know how your stress response system works.

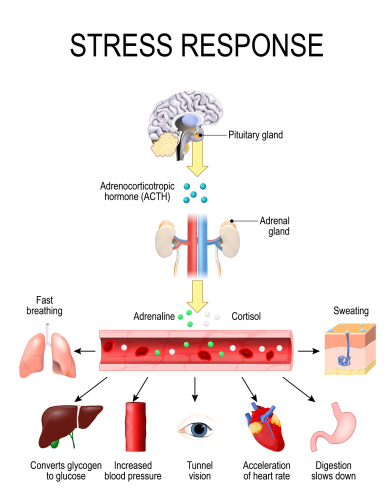

Stress is designed to help you. When our ancestors ran into a tiger, the stress response system gave them the energy and focus to either attack and kill the tiger or run away. This “fight or flight” response was critical for survival. This is still important today when you need to act to respond to a threat or take on a challenge. When you perceive a challenge, your body automatically responds by going through a rapid sequence of changes to increase your chance of success.

- Your body releases the stress hormones adrenaline (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and cortisol, which act as messengers that signal the rest of your body to prepare for action.

- Energy sources (glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids) rapidly mobilize from where they’re stored to critical muscles. This helps prime your body for action and keeps your brain alert so you can react quickly.

- Your heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing increase to speed the transport of nutrients and oxygen to your muscles and brain (to help protect your body). At the same time, energy normally used for longer-term processes—such as growth, digestion, and reproduction—is diverted to more immediate needs.

- Your muscles tense to provide your body with extra speed and strength, your pupils dilate to sharpen your vision, and perspiration increases to prevent overheating from your increased metabolic rate.

- Your immune function also gets a short boost of energy in anticipation of possible injury and infection.

So basically, the stress response system is a set of tools your body uses to provide the energy you need to perform. This ranges from helping you fight or flee a potential danger, get motivated for a challenge, reach out to help others or ask for help, and learn and grow from difficult experiences. This is a good thing. The problem is, not all tools work the same way in all situations. Some tasks need a “chainsaw” approach and others need “scissors.” So, if your body is reacting as if a tiger is chasing you when you’re helping your daughter with difficult math homework, you’re not setting yourself up for success. The goal of this system is to supply energy where you need it, when you need it. Your beliefs about stress can help this process, or they can get in the way.

How believing “stress is harmful” can undermine the body’s stress response

If you believe “stress is bad for me and I should avoid it at all costs” or “stress makes me weak,” then you likely associate the physical and psychological sensations that come with the stress response as harmful. In some cases, the nervous emotions and physical sensations that come with stress actually become threats themselves. This then causes the stress response system to go into overdrive and harm your performance and health. Another result of believing stress is bad and harmful: You’re more likely to turn inward and isolate yourself or avoid all challenges, depriving yourself of opportunities to learn or take on new challenges. This mindset also can impact your physiology. For example, when your heart starts pumping harder, it’ll likely cause more constriction and inflammation in your blood vessels.

How believing “stress is helpful” can help you to get the most out of stress

On the flip side, if you believe “stress is helpful for me and I should embrace it” or “stress makes me stronger,” you’re more likely to be able to channel the stress response to help you be more motivated and focused. Seeing the stress response this way allows you to use stress to build competence, strengthen social connections, and integrate lessons learned so you can be better prepared for the future. When your mindset embraces stress, the physiological impact is different too. In this case, when your heart starts pumping harder, your blood vessels are likely to relax and have less inflammation, and your heart pumping mimics exercise, which can help strengthen and boost your cardiovascular health.

![]() Strategy: When you notice the impact of the stress response system on your body, come up with a short “stress is good” motto to help you remember that what you’re feeling is your body’s way of helping you to perform. Here are a few examples:

Strategy: When you notice the impact of the stress response system on your body, come up with a short “stress is good” motto to help you remember that what you’re feeling is your body’s way of helping you to perform. Here are a few examples:

“This is just my body giving me the energy I need to perform”

“I am excited to take on this challenge”

“I feel like this because this is important to me, and my body is in it with me”

How to develop the belief “stress is helpful”

If you want to change a belief, you need to challenge it with evidence. Understanding how the stress response system works is an important first step, but changing a deeply held belief is easier said than done. This can be difficult when it comes to the belief that stress is harmful, because you might have vivid memories of past experiences where nerves got the best of you. The negativity bias makes you more likely to hold onto negative memories over the many benefits of stress in the past. Recognizing the benefits of stress can be hard to do because either you’ve been taught to avoid it, or you’ve been so stressed for so long it just seems normal.

Use the following questions to help you remember past experiences of stress and how stress helped you perform. For each question, try to find 1–2 vivid, meaningful examples. Reflect on what you learned about how the stress response system works—and how it played a role in each situation.

- Describe a time when you were at your best under pressure. Describe how you focused your attention, what emotions you experienced, what your self-talk was. What helped you to perform?

- Briefing a 2-star general. My attention was on making sure I was clear and concise stating the critical information that needed to be shared. I was a little nervous but was also somber and serious due to the severity of the brief. My self-talk was “This is important information and it’s my duty to my country to be the one to state it.” Practicing numerous times, and imagining what the experience would be like helped me to perform at my best when the time came.

- What is a personal value that’s extremely important to you that you live out each day? How does your stress response help you to live out this value?

- Loyalty is extremely important to me. At times when I begin to act in a way I might consider disloyal, I often feel it in my body before I even realize it in my mind. I’ll get butterflies in my stomach and feel my hands shake slightly. This helps me realize I need to change course.

- Describe a goal you accomplished that you cherish most. How did your stress response help you to succeed?

- Getting promoted was an extremely important goal to me. My stress response motivated me to make sure I was doing everything I could to set myself up for success. It wasn’t fun, and the stress leading up to the promotion board made me prepare extremely hard, but it was well worth it.

- Describe the most important relationships in your life. How does your stress response help you be there for them?

- My children are the most important people in my life. I worry about them constantly, and second guess myself when I’m with them, but it helps me to make sure I’m being the best parent I can be and doing all I can to protect them.

- Describe a stressful period of your life where you experienced significant growth. How did your experience of stress assist your growth?

- My divorce was extremely hard, but I learned through it that I haven’t been the person I want to be for the past few years. I have been incredibly selfish, and took a lot for granted. It was a horrible experience, but it helped me get my priorities in order, and be a better parent and a better leader. I’m now less judgmental when other people are struggling and I realize I have a lot to offer.

![]() Strategy: Write down your answers or find a picture or symbol that represents them so you can revisit them again to help solidify the belief that stress is helpful. Also, consider choosing a couple of these questions that you like and reflect on them each morning to prime your stress response system and help you be at your best.

Strategy: Write down your answers or find a picture or symbol that represents them so you can revisit them again to help solidify the belief that stress is helpful. Also, consider choosing a couple of these questions that you like and reflect on them each morning to prime your stress response system and help you be at your best.

- What are the values you want to live out today? How can your stress response system help you?

- What goals do you hope to accomplish today? How can your stress response system help you?

- Who are the people you want to care for today? How can your stress response system help you?

- What adversities might you face today? How can your stress response system help you?

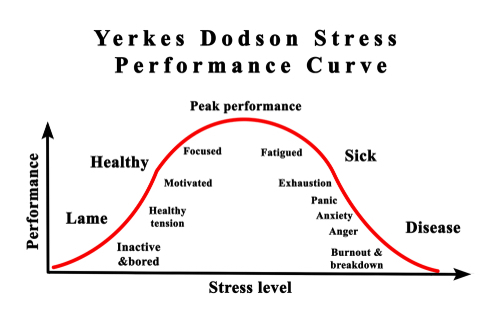

Finding the stress sweet spot

For each specific performance, each person has a certain “right” amount of energy they require from the stress response system that enables them to perform at their best. This is often known as your Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF). With too little stress, you won’t be engaged enough, but if you have too much stress, you might lose focus and control and break down. This “right” amount of energy is different for each person and each task. For example, an impending deadline on a work project, your child having trouble with other kids at school, a car accident, and a passionate kiss with your spouse will all activate your stress response system, but each require a different level of energy, focus, and emotion for you to be at your best. What allows you to perform at your best while giving a brief won’t be the same as what enables your battle buddy to do the same task.

For each specific performance, each person has a certain “right” amount of energy they require from the stress response system that enables them to perform at their best. This is often known as your Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF). With too little stress, you won’t be engaged enough, but if you have too much stress, you might lose focus and control and break down. This “right” amount of energy is different for each person and each task. For example, an impending deadline on a work project, your child having trouble with other kids at school, a car accident, and a passionate kiss with your spouse will all activate your stress response system, but each require a different level of energy, focus, and emotion for you to be at your best. What allows you to perform at your best while giving a brief won’t be the same as what enables your battle buddy to do the same task.

![]() Strategy: Help yourself stay in your stress “sweet spot” by using these 3 steps to help you have the right amount of energy to perform at your best.

Strategy: Help yourself stay in your stress “sweet spot” by using these 3 steps to help you have the right amount of energy to perform at your best.

- Step 1: Name the stress. This helps you break out of the primitive/reactive part of your brain and helps you to use the part that helps you plan and reflect.

- What are you feeling, doing, focusing on? What is your self-talk?

- Step 2: Embrace the stress. You’re experiencing stress because something you care about is in play and your body is trying to give you the energy needed to live it out.

- What goal or value makes this important to you?

- Step 3: Channel the stress. Use the energy your body is providing to intentionally improve your performance for the task at hand.

- What’s the best way to use your energy to help achieve that goal or value?

- What do you need to do, feel, or focus on?

- What do you need to say to yourself to get you there?

When should I pump the brakes on stress?

Stress can help you to perform at your best, but at times you might have too much energy for the current task, or your stress response system might have been activated for too long and is wearing you down. Luckily, your body has another natural mechanism. The relaxation response works in tandem with your stress response system to help you get the right level of stress to perform. The relaxation response helps reduce heart, breathing, and metabolic rates, as well as blood pressure and muscle tension. It also increases your feelings of positive mood and calm, and decreases inflammation. You can activate your relaxation response by using any of these mind-body skills.

- Mindfulness training, the practice of training your brain to stay in the present moment, offers many benefits. Practicing mindfulness can help you relax, lower your blood pressure, sleep better, become more focused and alert, and tune in to your body to perform better.

- Tactical breathing is a method of using your breath to change how you feel physically and emotionally to focus your attention and improve your performance. Breathing is one of the most basic human activities, and learning to control it strategically can lower your stress.

- Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is a way to relieve the physical symptoms of stress and anxiety (that show up as tight, aching muscles) by systematically tensing and releasing certain muscle groups in your body.

- Autogenic training is a mind-body strategy to combat stress. It requires you to focus on the feeling of your own breathing or heartbeat and imagine your body as warm, heavy, and/or relaxed. First, without judging, you concentrate on how warm or cool your hands are. Then, you imagine warmth in your hands and feet until you feel the sensations really happen.

- Yoga is a mind-body (sometimes called a “meditative-movement”) activity that uses a series of postures, breathing techniques, and relaxation practices to promote spiritual, mental, and physical health.

All of these are skills, and the more you practice them, the better you’ll become at using them to help pump the brakes on your stress.

![]() Strategy: Try using the Relaxation Response Skill Practice Tracker worksheet to find one that works best for you and track your progress.

Strategy: Try using the Relaxation Response Skill Practice Tracker worksheet to find one that works best for you and track your progress.

Notice your triggers of the “stress is bad” mindset and adjust fire.

One final way to help develop the belief that stress is helpful AND make stress helpful is to recognize the reactions to stress you might have when you believe stress is bad. If you believe stress is bad for you, then you will react to the experience of stress itself as a stressor. This will lead you to try and fight or flee the stress. Here are some common triggers that will let you know you’re falling into a “stress is bad” pitfall reaction—and strategies to help you adjust fire.

Trigger 1: Fleeing the stressor

Trigger 1: Fleeing the stressor

If you believe stress is bad for you, then it makes sense to want to avoid stress at all costs. That will likely lead you to trying to escape the stressor through some other activity. For example, have you ever had an important project you need to do that’s stressful, and you keep coming up with mindless ways to procrastinate? Some other examples include:

- Eating when not hungry

- Escaping through social media

- Binge watching TV or videos online

- Shopping

- Drinking alcohol or taking drugs

- Gambling

- Smoking

- Playing video games

These activities release dopamine, which provide a short-term experience of escape and feeling good, but will leave you unsatisfied and wanting more. Therefore, you often don’t feel energized or refreshed after engaging in them. Further, they can leave you feeling more stressed, because whatever the stressor was that you were escaping is still there.

![]() Strategy: Making “me-time” to help you stay refreshed and energized is important to maintaining your resilience, performance and well-being, but some “me-time” activities are better than others. Try exercise, prayer, going for a walk outside, or spending time doing a hobby that will generate positive emotions. Each of the relaxation response skills are effective as well.

Strategy: Making “me-time” to help you stay refreshed and energized is important to maintaining your resilience, performance and well-being, but some “me-time” activities are better than others. Try exercise, prayer, going for a walk outside, or spending time doing a hobby that will generate positive emotions. Each of the relaxation response skills are effective as well.

Trigger 2: Fighting the stressor

Trigger 2: Fighting the stressor

If you believe stress is bad for you, then it makes sense to get angry at whatever is bringing you additional stress. Unfortunately, it is usually the things that you care about the most that bring you stress. Because if you didn’t care, you wouldn’t be stressed. This can cause you to see opportunities and responsibilities incorrectly as a trespass and lash out when you shouldn’t. For example, do you catch yourself getting angry at work assignments that are your responsibility? Or notice you feel everyone else is an idiot doing things wrong which causes you to be frustrated often?

![]() Strategy: Try practicing gratitude to help you notice the good in others and the opportunities you are provided. Also optimism can help you to focus on what you need to do to take purposeful action, rather than being distracted by things outside of your control.

Strategy: Try practicing gratitude to help you notice the good in others and the opportunities you are provided. Also optimism can help you to focus on what you need to do to take purposeful action, rather than being distracted by things outside of your control.

Trigger 3: Distancing yourself from others

Trigger 3: Distancing yourself from others

If you believe stress is bad, and you are stressed, then it makes sense for you to distance yourself from others because you either don’t want to bring your stress to them, or you see them as a distraction from the more important stressors you need to deal with. Unfortunately, connecting with other people is one of the most important ways to optimize stress. When you know you have the support of others, it is much easier to handle challenges, and other people help you experience positive emotions, which help to buffer against the potential negative effects of stress.

![]() Strategy: When stressed take advantage of opportunities to discuss with others things they are excited about or interested in and then use Active Constructive Responding to share in their joy which will build your relationship. It will also help you to relieve your stress and feel energized to handle the stressors at hand.

Strategy: When stressed take advantage of opportunities to discuss with others things they are excited about or interested in and then use Active Constructive Responding to share in their joy which will build your relationship. It will also help you to relieve your stress and feel energized to handle the stressors at hand.

Bottom line

Stress can be good for you if you believe it’s good for you. But developing a new belief takes time and effort. Each day, try to find a time in your normal routine to remind yourself you’ll experience stress today—and that stress will help you to perform and grow at the things that mean the most to you.

If you have additional questions about stress, or would be interested in a free stress optimization webinar for Military Service Members, family members, or healthcare providers, use HPRC’s Ask the Expert form.