Temporary separations are unavoidable in military life. Examples of times a Service Member will be away from their children include deployments and TDYs. Children react differently when one parent becomes temporarily unavailable, depending, at least to some extent, on their “attachment style.”

Attachment styles are the ways we react when we are separated from and later reunited with those in our close relationships. They help explain how we interact with others, especially our closest relationships. A person establishes their attachment styles in infancy, and their style tends to remain relatively stable the rest of their life.

The following is an overview of attachment styles, with a focus on how children with different attachment styles react to temporary separations from their Service Member parent.

Overview of attachment styles

Attachment styles are important because they set the stage for how children view:

- The dependability of others

- Themselves as lovable

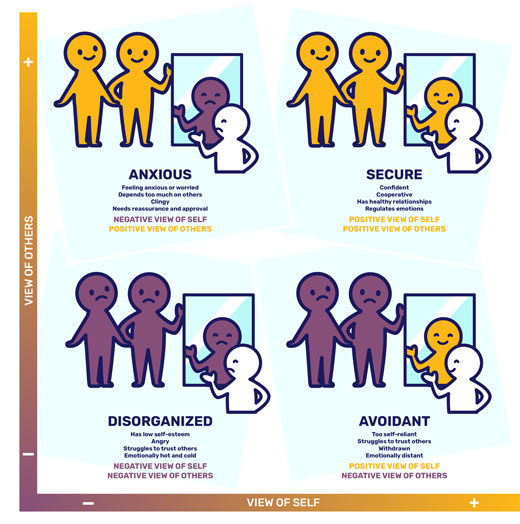

Only one attachment style is labeled “secure,” but 3 attachment styles fall under the category of “insecure”: anxious, avoidant, and disorganized.

Secure attachment style

Children with a secure attachment style trust both themselves and others. They believe they are capable of helping themselves, but they also believe they can rely on the help of others. They have high self-esteem, trust in others, cooperate with others, and show helpfulness toward others.

Parents of children with a secure attachment style are available to their child and responsive to their child’s needs.

Insecure attachment styles

Anxious. Children with an anxious attachment style depend too much on close relationships. Their self-esteem depends heavily on relationships, and they only feel worthwhile when they have close relationships. Even though they rely on their close relationships, they also fear being abandoned by those they are close to. They also display anxiety and immaturity.

Parents of children with an anxious attachment style are primarily focused on their own selves and anxieties instead of their child’s. They are also inconsistent in responding to their child’s needs.

Avoidant. Children with an avoidant attachment style trust themselves but not others. They are so self-sufficient that they shun closeness. They also tend to distrust others.

Parents of children with an avoidant attachment style reject their child’s needs, are distant or standoffish, and are uncomfortable with human touch and bodily contact.

Disorganized. Children with a disorganized attachment style fear closeness, even though they might know they need relationships to survive. They find it difficult to open up because they’re afraid of rejection and abandonment. They also have low self-esteem, poor emotional regulation, and fear of being rejected.

Parents of children with a disorganized attachment style are often depressed, abusive (that is, they threaten to not love the child if the child doesn’t behave in certain ways), and troubled by their own unresolved attachment-related traumas.

How children with different attachment styles react to temporary separations

During temporary separations, children rely heavily on the at-home parent or other caregiver for security and reassurance. In general, when separated from a deployed parent, children respond positively when they are given opportunities to:

- Adopt more responsibilities

- Gain independence

- Grow in maturity

Many children, whether they have secure or insecure attachment styles, show signs of distress when the Service Member parent leaves. However, separations can be particularly difficult for children with insecure attachment styles because they already had issues with trust and rejection.

A child with a secure attachment might or might not show distress when separated from their parent.

A child with an anxious attachment often shows high levels of distress when separated from their parent. The child might even have shown signs of distress before separation.

A child with an avoidant attachment will show little or no distress when separated from their parent.

A child with a disorganized attachment often shows high levels of distress when separated from their parent.

How children with different attachment styles react to reunions

It’s normal for both secure and insecure children to feel joy and anxiety upon reunion, as well as some degree of uncertainty, anger, and emotional disconnection. Very young children might have no memory of the Service Member and might initially react to the returning parent as they would to a stranger.

A child with a secure attachment will seek to be close to the Service Member upon reunion, will be happy to see them, and can be consoled by them. Such children are very adaptable and resilient. They will naturally pick up their positive relationship with the Service Member upon reunion.

A child with an anxious attachment will also seek to be close to the Service Member upon reunion but will also show anger toward them. The parent might not be able to console the child upon reunion.

A child with an avoidant attachment will not try to be close to the Service Member upon reunion. Instead, they will actively avoid contact or ignore them.

A child with a disorganized attachment will show contradictory or conflicted behavior upon reunion with the Service Member. The child might…

- Show indifference towards the parent’s reappearance.

- Seek to be close to a stranger instead of the parent.

- Appear dazed.

- Be indecisive (that is, unable to choose between going toward or going away from the parent).

- Display fear upon seeing the parent.

In short, children with insecure attachments—anxious, avoidant, or disorganized—to the Service Member before deployment are at greater risk for problems. They might feel heightened levels of separation anxiety, depression, or anger.

If you are interested in learning more about how to manage deployments and separations, read these other HPRC resources: