Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a therapeutic method used to treat trauma. Developed about 20 years ago, EMDR has become more common as a way to address and treat the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although the research is mixed on whether EMDR is as effective as other more traditional types of combat trauma therapy, the Department of Defense and Veterans Health Administration accept EMDR as a valid treatment for Service Members with post-traumatic stress.

How does EMDR work?

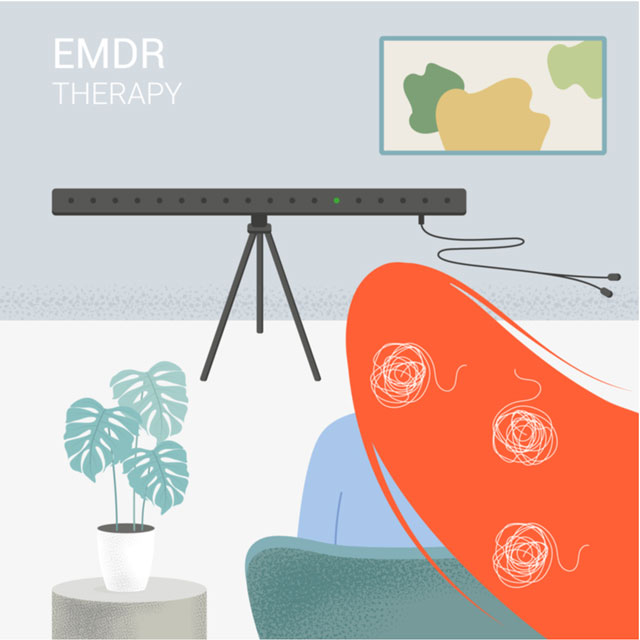

When a patient is treated with EMDR, they’re asked to remember and talk about a traumatic memory while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus. So, while the patient discusses a past memory, they also visually track the horizontal movement of an object (such as light or the therapist’s finger) as it moves in a specific way. The horizontal tracking is a “bilateral” stimulation thought to create a unique effect in the brain that other types of eye movements (such as vertical movement) don’t.

When a patient is treated with EMDR, they’re asked to remember and talk about a traumatic memory while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus. So, while the patient discusses a past memory, they also visually track the horizontal movement of an object (such as light or the therapist’s finger) as it moves in a specific way. The horizontal tracking is a “bilateral” stimulation thought to create a unique effect in the brain that other types of eye movements (such as vertical movement) don’t.

Certain parts of the brain react to threats and danger, while other parts interpret, make sense of, and process those dangers. Consider what happens when you trip on the stairs: Before you have a chance to consciously think, “Oh no, I’m falling, I’d better grab the hand rail!” your body reacts for you. Once you regain your footing, your brain has a chance to make sense of what just happened, such as “I slipped, but I’m okay.” Because things calmed down after you slipped, your brain processes it and moves on.

But when someone goes through trauma, sometimes the experience doesn’t get to the processing part of the brain. Instead, the memory continues to live in the reacting part of the brain. So, when a person sees, hears, or even smells a trigger similar to the original traumatic event, the emotional and physical reactions are the same as the first time. (For example, the smell of diesel fuel can bring back memories of active tanks; the sound of firecrackers might bring on memories of shots firing.) These reactions can cause extreme distress and make everyday life difficult.

When Service Members are in combat, the threat is often prolonged and extreme, so there isn’t always a chance for the experience to leave your reacting brain—or process properly. The goal of EMDR is to address traumatic memories that weren’t adequately processed and the way the associated emotions are stored in the brain. The objective is to temper the negative emotional experience when memories are triggered.

The primary theory for how EMDR treatment reprocesses the emotions associated with memories is based on the idea that the brain (and working memory) can only do so much at once. So, when directing your attention in 2 ways (talking about an experience while following something with your eyes), your brain has less bandwidth for the memory to have its “full effect.” As a result, some those traumatic memories become less vivid and less distressing. The recommended number of EMDR treatment varies, but usually occurs over 6–12 sessions.

Is it right for me?

EMDR has shown some success in treating certain types of post-traumatic stress (resulting from sexual abuse, car accidents, and natural disasters, for example). The question is whether it can be helpful specifically for Service Members—mostly because combat stress is unlike many other types of trauma. Everyone responds differently to treatment, and more research in needed to understand how EMDR stacks up against other treatment options for Service Members. There are also several other types of treatment recommended by DoD and VA for PTSD in addition to EMDR. It’s unclear whether EMDR treatment is better than other types of trauma treatment, but it is clear EMDR is better than no treatment at all. So, if you’re exploring treatment options, talk to your healthcare provider for more information.