If you’re experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), it’s important to understand how the different parts of your brain function. Post-traumatic stress is a normal response to traumatic events. However, PTSD is a more serious condition that impacts brain function, and it often results from traumas experienced during combat, disasters, or violence.

Your brain is equipped with an alarm system that normally helps ensure your survival. With PTSD, this system becomes overly sensitive and triggers easily. In turn, the parts of your brain responsible for thinking and memory stop functioning properly. When this occurs, it’s hard to separate safe events happening now from dangerous events that happened in the past.

Background

Over the past 40 years, scientific methods of neuroimaging have enabled scientists to see that PTSD causes distinct biological changes in your brain. Not everybody with PTSD has exactly the same symptoms or the same brain changes, but there are observable patterns that can be understood and treated.

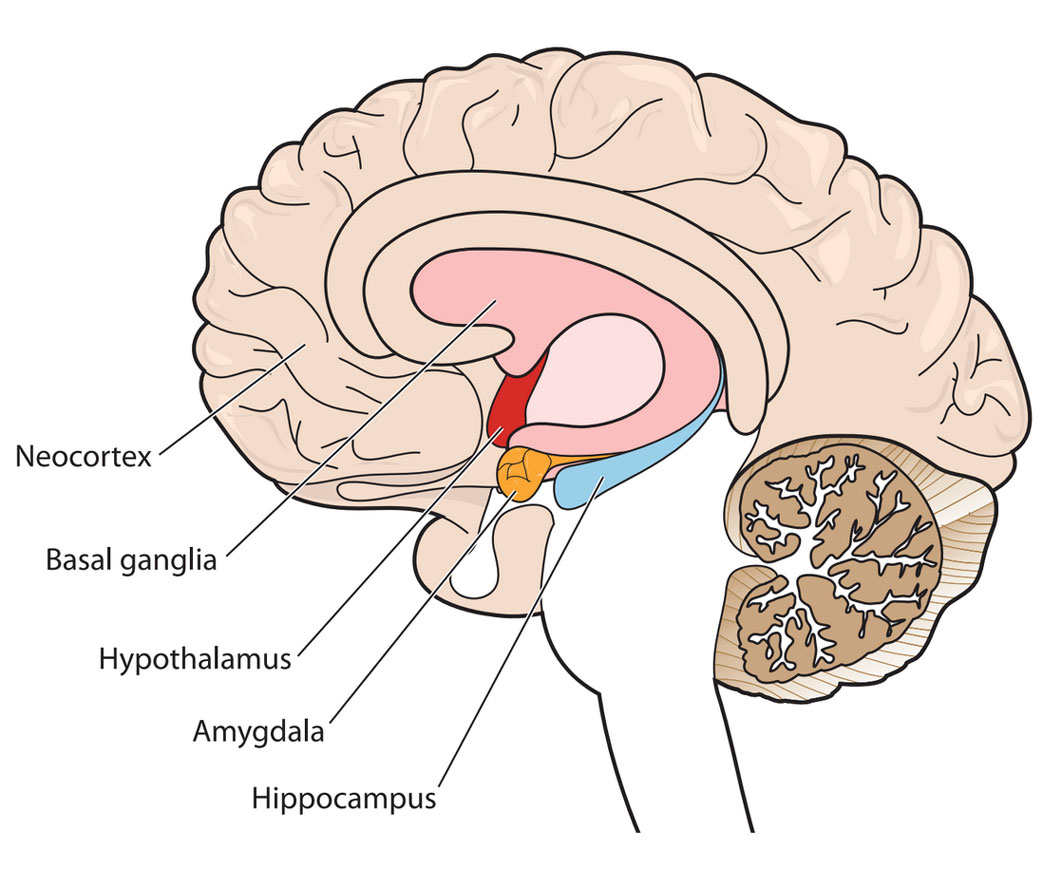

The diagram shows a cross-section of the brain parts discussed here.

Your alarm system

Your amygdala triggers your natural alarm system. When you experience a disturbing event, it sends a signal that causes a fear response. This makes sense when your alarm bells buzz at the right time and for the right reason: to keep you safe. Those with PTSD tend to have an overactive response, so something as harmless as a car backfiring could instantly trigger panic. Your amygdala is a primitive, animalistic part of your brain that’s wired to ensure survival. So when it’s overactive, it’s hard to think rationally.

Your brake system

Your prefrontal cortex (the front-most part of your neocortex) helps you think through decisions, observe how you’re thinking, and put on the “brakes” when you realize something you first feared isn’t actually a threat after all. Your prefrontal cortex helps regulate emotional responses triggered by the amygdala. In Service Members with PTSD, the prefrontal cortex doesn’t always manage to do its job when needed.

A bad combination

An overactive amygdala combined with an underactive prefrontal cortex creates a perfect storm. It’s like stomping on your car’s accelerator, even when you don’t need to, only to discover the brakes don’t work. This might help you understand why someone with PTSD might: (1) feel anxious around anything even slightly related to the original trauma that led to the PTSD; (2) have strong physical reactions to situations that shouldn’t provoke a fear reaction; and (3) avoid situations that might trigger those intense emotions and reactions.

System recall errors

Other common PTSD experiences—such as unwanted feelings that pop up out of nowhere or always being on the lookout for threats that could lead to more trauma—seem to be related to the hippocampus, or memory center of your brain. Your hippocampus is a lot like your computer’s memory that writes files to its hard drive. After a trauma, your hippocampus works to remember the event accurately and make sense of it. But because a trauma is typically overwhelming, all the information doesn't get coded correctly. This means that you might have trouble remembering important details of the event, or you might find yourself thinking a lot about what happened because your hippocampus is working so hard to try to make sense of things.

Learn more

Your amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus all contribute to the feelings and actions associated with fear, clear thinking, decision-making, and memory. Understanding how they work also might explain why some therapies can help you work through PTSD. To find out more about how your brain works, check out our series on Warfighter brain health.