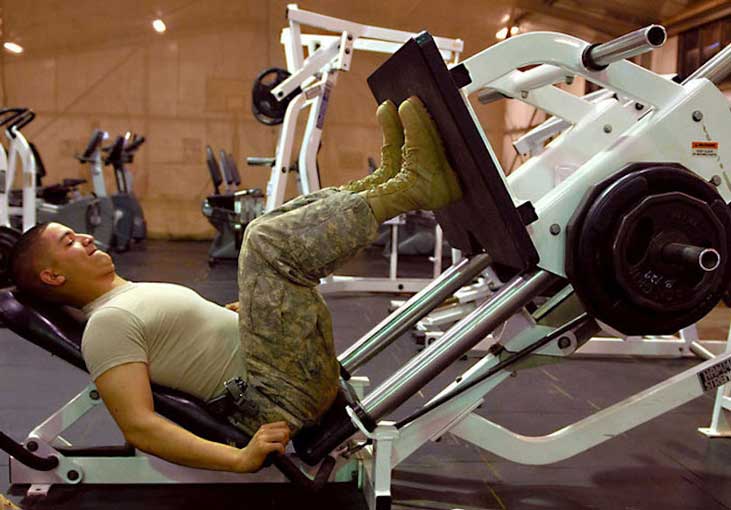

Getting fit or staying fit on deployment can be a challenging task. For some, working out regularly is the only thing they have to do in their free time. For others, making time or taking the opportunity to work out is a challenge. When it comes to deployment PT, here are a few best practices everyone should follow to stay injury-free and some tips for when facilities and opportunities to work out are lacking.

Prevent injuries on deployment

Injuries to muscles, bones, ligaments, and tendons—also called musculoskeletal injuries (MSK-I)—on deployment are an important issue for Service Members and their commands. During Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, non-battle MSK-Is were the number-one reason for MEDEVAC from theater. About 35% of all MEDEVACs were due to MSK-Is, compared to 18% from battle injuries. Most of the former happened during physical training and recreational sports.

Many injuries during PT are due to overtraining and extreme conditioning. Overtraining occurs when you’re training at a frequency and intensity that doesn’t allow your body enough time to recover from the exertion of exercise. It’s important to allow for enough rest, both between exercise sets and between workout days. You should allow 48–72 hours between workouts that focus on the same muscle groups.

Extreme conditioning programs are defined by inadequate rest in between sets. These can lead to career- and life-threatening conditions such as exertional rhabdomyolysis. To avoid turning your high-intensity workout into extreme conditioning, keep your total exercise volume (number of reps x number of sets) and set times reasonable. For example, high-intensity circuits should have a maximum length of 1–2 minutes, depending on the exercises performed. Be sure to get enough rest between sets. Experts typically recommend a total of 4–8 sets of exercises per muscle group during a workout, with the number of reps in each set based on your workout goal. For example, do 12–15 reps for muscular endurance or 6–10 reps for muscular strength.

For more acute injuries that aren’t necessarily due to overtraining, such as ankle sprains during recreational sports, performing an injury-prevention dynamic warm-up before all PT will help reduce your injury risk. For example, a group of 20 people who play a sport weekly and perform an injury-prevention dynamic warm-up before playing can prevent 1 or 2 injuries over a 3-month period. That translates to preventing up to 10 injuries for a company over 3 months of deployment.

Preventing injuries over the course of a deployment is a force multiplier when it comes to unit readiness too. Even if injuries aren’t severe enough to require MEDEVAC from theater, fewer injuries mean more people are ready for daily missions. More people available allows for more rest and recovery for those who aren’t working and more people available to cover down when someone does get hurt. The hardest part of doing an injury-prevention program (IPP) isn’t doing it yourself—it’s getting others in your unit to do it as well. IPPs are a numbers game, meaning the more people who do them and the more time that’s spent doing them, the better they work.

Deployment fitness tips

If you have limited time, equipment, or other resources, staying fit can be difficult. However, recent research shows that you can actually maintain your fitness for a few months while dedicating minimal time to PT. For cardio exercise, most moderately fit people can maintain their fitness for up to 15 weeks by exercising as little as twice a week or by shortening training sessions to as little as 13–26 minutes. Strength and muscle size can be maintained even longer—up to 32 weeks. For people younger than 35, this can be exercising as little as once a week by performing one set per exercise. For people older than 60, sessions twice a week with 2–3 sets per exercise should be enough. The key for both cardio and strength training is to maintain the same level of intensity, using heart-rate zones as a guide for cardio and a percentage of your one-rep max for strength training.

If equipment is your main limitation, you might need to get creative with what you use for weights. Water bottles and ammo cans can be filled with sand, or a loaded ruck can be used for weighted squats or lunges. You can also modify bodyweight exercises to make them more challenging. Elevating your feet during push-ups or putting a foot up on a bench behind you for lunges (called a Bulgarian split squat) can make those exercises more challenging if regular bodyweight exercises aren’t enough. Read HPRC’s limited-equipment article for more ways to get creative without a full gym.

For more tips, read HPRC’s blog about working out while deployed from Dr. Myro Lu, a physician who deployed with the 98th Civil Affairs (Airborne) Battalion and 4th Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne).