When Service Members don’t eat or drink enough calories to meet their energy demands, performing optimally is unlikely. In particular, not getting enough carbohydrates (carbs) could cause a negative energy balance. Negative energy balance or “underfueling” occurs when Warfighters use more energy than they take in. Underfueling can result in poor performance, fatigue, “hitting the wall,” weight loss, a decrease in motor skills or concentration, and perhaps injury.

Daily fueling

After eating or drinking carbs, the body breaks them down into glucose (sugar), which is released into the blood stream. Unused glucose is stored in the muscles and liver as glycogen. At rest, the brain and central nervous system use most of the body’s blood glucose, while muscles use less than 20%.

Fueling for exercise

Carbs are the body’s preferred fuel for exercise. Muscle glycogen, the major source of carbs in the body, and blood glucose provide half of the energy for moderate-intensity exercise and 2/3 of the energy for high-intensity exercise. The muscles use more glucose with longer and more intense exercise than with low intensity exercise. Blood glucose becomes an increasingly important source of fuel as muscle glycogen stores decline. There’s an increased need for carbs to support the working muscles and prevent fatigue.

The approximate amount of stored carbs in the body are as follows:

- Muscle glycogen provides 300–400 g of carbs or 1,200–1,600 calories

- Liver glycogen provides 75–100 g of carbs or 300–400 calories

- Blood glucose provides 5 g of carbs or 20 calories

The body’s carbohydrate stores are relatively limited to support sustained exercise. For example, liver glycogen stores, which kick in when blood glucose is low, can be depleted by a 15-hour fast, such as between dinner the night before to the first meal the next day. This highlights the need for getting enough carbs, especially during periods of prolonged, intense, or frequent exercise.

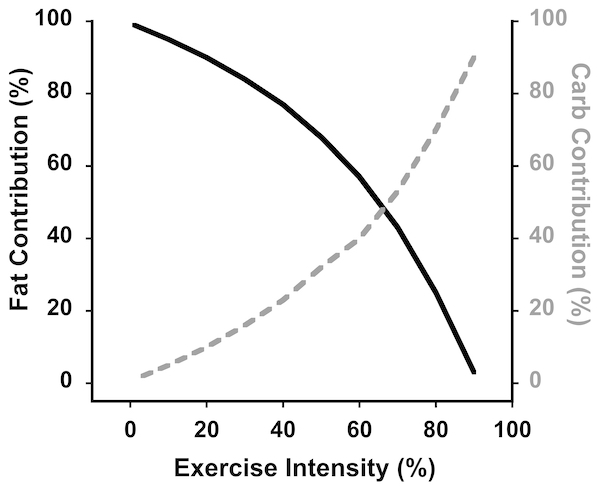

Fat stores play a role in fueling too, especially for low-intensity or long duration exercise. As exercise intensity increases, the body relies more on carbs and less on fat for energy.

Underfueling

Service Members who underfuel end up with low carb stores, or “low carbohydrate availability” to provide the energy they need. There are many reasons why a Service Member might underfuel:

Intentional:

Intentional:

- Limiting calorie intake

- Trying to lose weight (such as prior to military physical fitness/readiness test)

- Following a new diet (calorie restriction, juicing, cleanse, low carb diet*)

- Increasing protein or fat to replace carbs

- Limiting certain types of foods or food groups, such as avoiding grains or gluten (due to allergies, for weight loss, etc.)

Unintentional:

- Greater training demands (amount, intensity, or type) without increasing carbs to match energy output

- Limiting meals or snacks due to lack of money, time, or other resources

- Limited availability of food due to traveling, moving (PCS), or schedule

- Lack of knowledge about food preparation and shopping

- Inadequate planning of meals and snacks

- Unsure how many carbs to eat

- Increase caloric demand due to environmental conditions (heat, cold, altitude)

*Note: The ketogenic (“keto”) diet is intentionally low in carbs and pushes the body to burn fat for fuel. New research suggests the body is able to adapt and perform most types of exercise when in a state of nutritional ketosis. Ketosis, when ketone bodies are used for fuel, is not the same as underfueling or having insufficient carbs. For more information on whether the keto diet is appropriate for you, speak with a registered dietitian (RD) or physician.

Got fuel?

The brain and working muscles compete for both circulating and stored glucose. Inadequate carbs can cause hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) when the muscles’ need for glucose is greater than what the liver can provide during exercise. Underfueling can occur from eating too few carbs or eating them at the wrong time. Too few carbs or skipping fueling opportunities before, during, or after exercise can impact performance. Also, failure to rebuild carb stores due to inadequate recovery fueling may prevent optimal performance.

Carbs as an essential part of an eating plan

Consuming enough carbs daily is essential to replenishing them in muscles and the liver for mission readiness. Providing the body enough carbs at the right time optimizes performance by having adequate “carbohydrate availability.”

Carbohydrates are found in a variety of foods. Many are nutrient-dense, containing healthy fats, protein, fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Carb-rich foods include:

Carbohydrates are found in a variety of foods. Many are nutrient-dense, containing healthy fats, protein, fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Carb-rich foods include:

- Grains: pasta, rice, cereal, oatmeal, bread, crackers, tortillas, popcorn, granola bars

- Starchy vegetables: potatoes, corn, peas, beans

- Dairy: yogurt, milk, soymilk

- Fruit: all fresh, frozen, dried, and juice varieties

- Veggies: all fresh and frozen varieties

- Sports foods and drinks: sports drinks, gels, “goos,” “blocks,” energy bars

Guide Service Members to fill 3/4 of their plate with nutrient-rich carbs. The need to increase or decrease carb-dense foods like grains and starchy veggies, and supplement with “sports foods” and drinks depends on the amount, type, duration, and intensity of the training—and fitness goals. If Warfighters eat the same amount of carbs on a “light” day vs. a “hard” day of intense or prolonged training, they risk underfueling.

To prevent underfueling and increase the chance of peak performance, educate Warfighters to include enough carbs in their daily eating plan, especially around exercise. General carb needs for fueling and recovery (adjust for individual training schedule, weight and fitness goals, and performance goals) are as follows:

To prevent underfueling and increase the chance of peak performance, educate Warfighters to include enough carbs in their daily eating plan, especially around exercise. General carb needs for fueling and recovery (adjust for individual training schedule, weight and fitness goals, and performance goals) are as follows:

- Light exercise (low-intensity of skill-based): 3–5g/kg (1.4–2.3g/lb)

- Moderate exercise (about 1 hour/day): 5–7g/kg (2.3–3.2g/lb)

- High exercise (endurance program ~1–2 hours/day moderate- to high-intensity): 6–8g/kg (2.7–3.6g/lb)

Meal planning can help ensure consistent and sufficient energy and carbohydrate intake. Carbs play a specific role in both fueling and recovery:

Meal planning can help ensure consistent and sufficient energy and carbohydrate intake. Carbs play a specific role in both fueling and recovery:

- Daily fueling: Maintain blood sugar, fuel the brain, power muscles, build carb stores

- Before: “Top off” fuel tank prior to exercise

- During (exercise >60 minutes): Provide carbs to maintain blood sugar and fuel working muscles

- After: Replenish fuel tank (muscle and liver glycogen stores) depleted during exercise

Tips to prevent underfueling:

- Focus on balanced meals of carbs, lean protein, and healthy fats.

- Create a meal plan—consider individual schedule, preference, and eating pattern (such as 6 mini meals or 3 larger meals with 2 smaller snacks).

- Keep high-fuel snacks on hand—pair carbs with protein- or fat-rich foods for balanced fueling (fruit + yogurt, whole grain crackers + peanut butter, dried fruit + nuts or seeds).

- Adjust calories and carb intake when training intensity, duration, and/or frequency increases. Quick and convenient options include: chocolate milk, homemade fruit smoothies, sports drinks, and “sports foods” such as, bars, gels, “goos,” and “blocks.”

- Focus on recovery fueling within 2 hours after exercise, trainings, or missions—at least 50 g carbs with 15–30 g protein.

Further concerns

Service Members with very low calorie intake, excessive weight loss, or chronic underfueling might be at risk for nutrient deficiencies (such as iron), Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), or an eating disorder. Female Warfighters might also be at risk for Female Athlete Triad. Service Members with these concerns should get a full medical assessment.

For more information on fueling around exercise, read:

For individualized nutrition recommendations, refer to a registered dietitian (RD), preferably a board-certified specialist in sports nutrition (CSSD).