The foundational movements of an exercise program are the most basic movements you perform, but they’re often parts of more complex movements or exercises too. Learning how to do these basic movements correctly can help prevent injuries and enable you to do more advanced movements as you get stronger. For example, first you would learn how to perform a deadlift, and then you would progress to do a clean, which requires you to hang with the weight once you’re stronger.

Foundational movements for the Warfighter

The most common movement patterns performed during military tasks and training are deadlifts, pulling, squats, pushes, carries, and lunges. You also need to engage and stabilize your core to do these movements safely and effectively. By working on these movements, you can increase your physical performance (strength, power, speed, coordination, etc.) and reduce your injury risk.

Below is a brief description of each movement pattern and an example of when you would typically use it. While the descriptions of the foundational movements in this article are very basic, the linked articles will provide more details and video demonstrations.

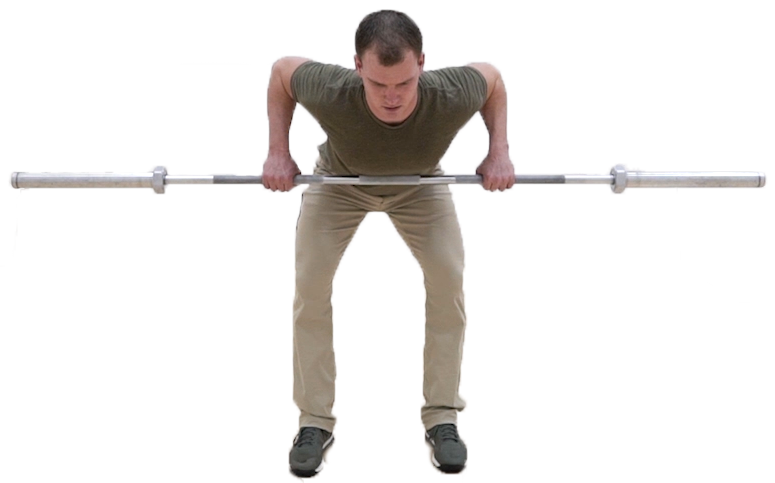

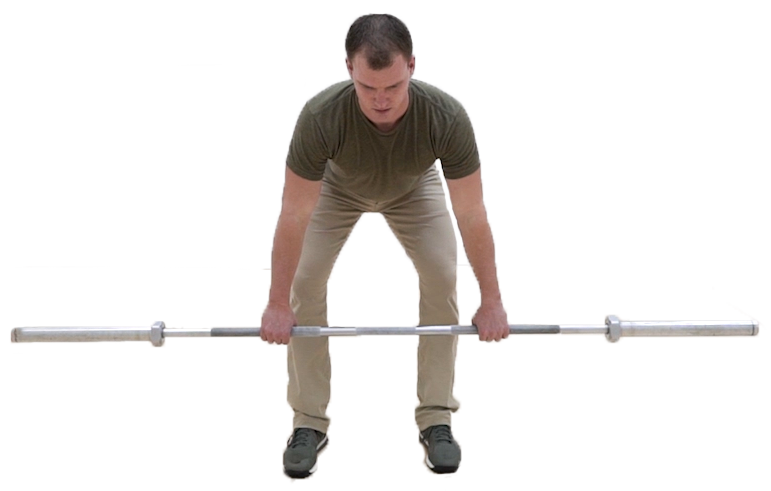

Deadlift

To perform a deadlift, bend at the hips and knees as you reach down, as if to pick up an object from the floor; then return to a standing position. Correct performance of this movement is especially important when the object you’re trying to pick up is heavy.

Pull

“Pulls” refer to movements that use your upper body both to pull objects toward you (such as rowing) or pulling your body toward something (such as a pull-up). You also can do more coordinated and sequential movements using your legs and hips together to pull objects up to your shoulders (such as cleans). To do pulling movements correctly, you need to stabilize your core and maintain proper posture. Some examples of times you would use pulls include pulling your body up and over a wall, climbing a rope, and lifting an object to your shoulder for easier carrying.

Squat

To perform an air squat, bend at the hips and knees, allowing your body to travel downward until the tops of your hips are below the tops of your knees; then return to a standing position. The most common example of a squat-like movement is going from a standing to seated position (or vice versa), such as a mechanic squatting to work on a wheel or an infantryman squatting to get under a barrier.

Push

Pushing refers to using your upper body to push objects away and your own body weight off something (such as a push-up). In some situations, you’ll need to use your legs and hips to generate power when pushing objects overhead or across a certain distance (such as pushing a sled). As with pulling movements, you’ll need to engage your core to maintain proper posture through the exercise.

Carry

The carry refers to carrying objects by your sides (such as farmers carries), on your back, at your chest, or across one shoulder. Some uses of carries include doing ambulatory drills, carrying a pack, and carrying other types of equipment (such as ammo cans).

Lunge

The lunge involves taking a long step forward, bending your front knee, and allowing your back knee to come close to the ground, while keeping your torso perpendicular to the ground throughout the movement. You use this movement any time you have to crouch down to one knee and when stepping up and down in different types of terrain.